Cover image: Sintesi Fascista by Alessandro Bruschetti

When the Italian poet and art critic Filippo Marinetti published the Manifesto of Futurism (Italian: Manifesto del Futurismo) in 1909, he advocated not only for a new style of art but also for the abolition of the past.

Filippo Tommaso Emilio Marinetti was born on December 22, 1876, in Alexandria, Egypt. He is widely considered the ideological founder of Futurism, a political, literary, and artistic movement.

Marinetti is best known for his futurist poetry which reflect his dynamic and energetic style. He was influenced just as much by political thinkers as he was by other artists. Among others, though, Marinetti was especially influenced by the French political thinker Georges Sorel.

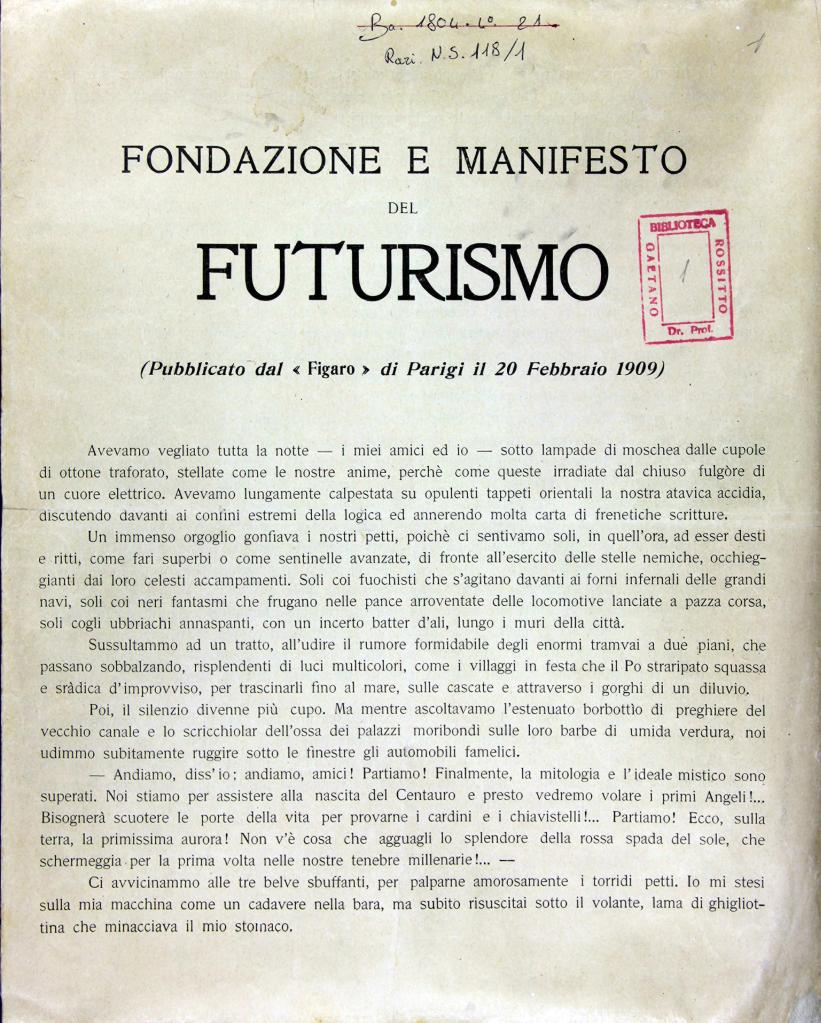

One of Marinetti’s most significant contributions is his Manifesto of Futurism (Italian: Manifesto del Futurismo), published in 1909. Within his manifesto, Marinetti proclaims what he believed to be the eleven tenets of the ideology behind futurist art. His first point was that the futurists “want to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness.” Unlike the world he considered to be neutered and weak, Marinetti and the futurists wanted to embrace the risks of life and the will to power. Marinetti furthers this sentiment, in which the futurists “declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath…a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

Artistic creations based on antiquity were outdated to the futurist and emblematic of an archaic past. Instead, Futurism is all about dynamism and motion. Common motifs of the futurists include automobiles, large ships, airplanes, and electrified cities. Yet going even further against antiquity, Marinetti wished to “demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.” To the futurists, what was static was in decay, and that’s how the futurists saw Italy. Italy needed rejuvenation, and rejuvenation required great energy and–ultimately–violence. A purging of degenerative beliefs and history was, in their view, necessary to liberate the souls and reach one’s full potential.

Marinetti goes on to write that “beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character.” Inferable from this rhetoric, Marinetti would be an early supporter of Italian fascism. He was, after all, the product of a new spirit in Italy. Fascism, which wouldn’t take control of Italy until 1922, was a budding ideology with great intellectual influence. Marinetti was an early follower of the movement, eventually co-authoring in 1919 the Fascist Manifesto. In line with fascist rhetoric, Marinetti explains that futurists “want to glorify war – the only cure for the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.” To Marinetti, it was through violence and bloodshed that greatness could be achieved, and it was through violence and bloodshed that beauty could be realized.

Ultimately, Marinetti was not a reactionary. He was not, either, a conservative. He was a revolutionary from the right, urging for the abolition of the past to free the soul. It is important not to file him into the larger group of reactionary fascists; it is easy to call him a reactionary simply because of his connections to fascism. To do so, however, is wrong, and makes one’s understanding of Futurism from the start muddied and fallacious. Because of this, I have decided to start my Futurism Series with Marinetti, who is for many the jumping-off point of the movement. Understanding him clearly allows one to more thoroughly understand and therefore better appreciate other futurist artists.

How Marinetti frames Futurism in his manifesto is no doubt extremely controversial. It is illiberal, advocating violence and war, and heavily critical of women. Regarding his framing of Futurism as a movement contemptuous towards women, I will address that in another article when I cover Valentine de Saint-Point, a French futurist painter and writer who wrote The Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (Italian: Manifesto della Donna futurista). It is important to understand that Marinetti did not have a total monopoly on Futurism’s meaning and that not all futurists agreed with Marinetti.

Considering the limitations of Marinetti’s analysis of Futurism, however, there is still great merit and learnings that one can acquire from reading his manifesto. He sets a general aesthetic blueprint for the movement and highlights what is at its heart: a focus on dynamism, the future, and revolution.

Leave a comment